Can Large Corporations Fuel the Growth of Black Owned Businesses?

Below is the Nowak Metro Finance Lab Newsletter shared biweekly by Bruce Katz.

Sign up to receive these updates.

July 16, 2020

(co-authored with Aiyah Josiah-Faeduwor and Avery Harmon)

Our recent analysis of the US Census Bureau’s 2018 Annual Business Survey revealed that there are 124,000 Black-owned employer firms in the US, representing only 2.2% of all employer businesses even though Blacks make up 14% of the US population.[1] Black-owned employer businesses are smaller, with fewer employees, lower average revenues, and lower average payroll expenditures, than businesses overall. That’s partly because these firms concentrate in sectors of the economy that pay less and offer fewer opportunities for productive growth.

We are heartened by the new energy emerging across multiple sectors to rectify these longstanding disparities. On June 30th, for example, Netflix committed $100 million to reduce the racial wealth gap, jumpstarting the effort with a $25 million partnership with the Local Initiatives Support Corporation. The Netflix commitment, like other corporate efforts over the years, has focused on providing Black entrepreneurs and businesses with greater capital access. This is essential given the structural racism that has permeated the financial sector for generations.

But focusing on the supply of capital is not sufficient. We believe that an equal level of attention must be given to the demand side of the business equation, namely the procurement of goods and services by the nation’s corporations, universities, hospitals, financial institutions and governments. Our strong conviction is that supplier diversity efforts, embedded for decades in federal law and private practice, have failed to realize their proclaimed objectives or stated goals. Over the next several months, my colleagues and I hope to bring transparency to “demand access,” a subject that rarely receives the kind of scrutiny as capital commitments and is often shrouded in corporate secrecy.

A little history is instructive. In response to the civil unrest sparked by the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., President Nixon established the foundation for the modern supplier diversity program by signing Executive order 11458, creating a host of programs including the SBA 8(a) minority set-aside program.[2] This order formalized the federal government’s commitment to minority-owned small businesses which was accelerated by President Carter and Black business leaders’ whose advocacy helped to fuel the earliest iteration of corporate supplier diversity.[3] The Detroit automakers, Chrysler, GM, and Ford, became early adopters of the program recognizing how supporting the rise of African-American workers would generate long-term benefits for the company, its stakeholders, and local community.[4]

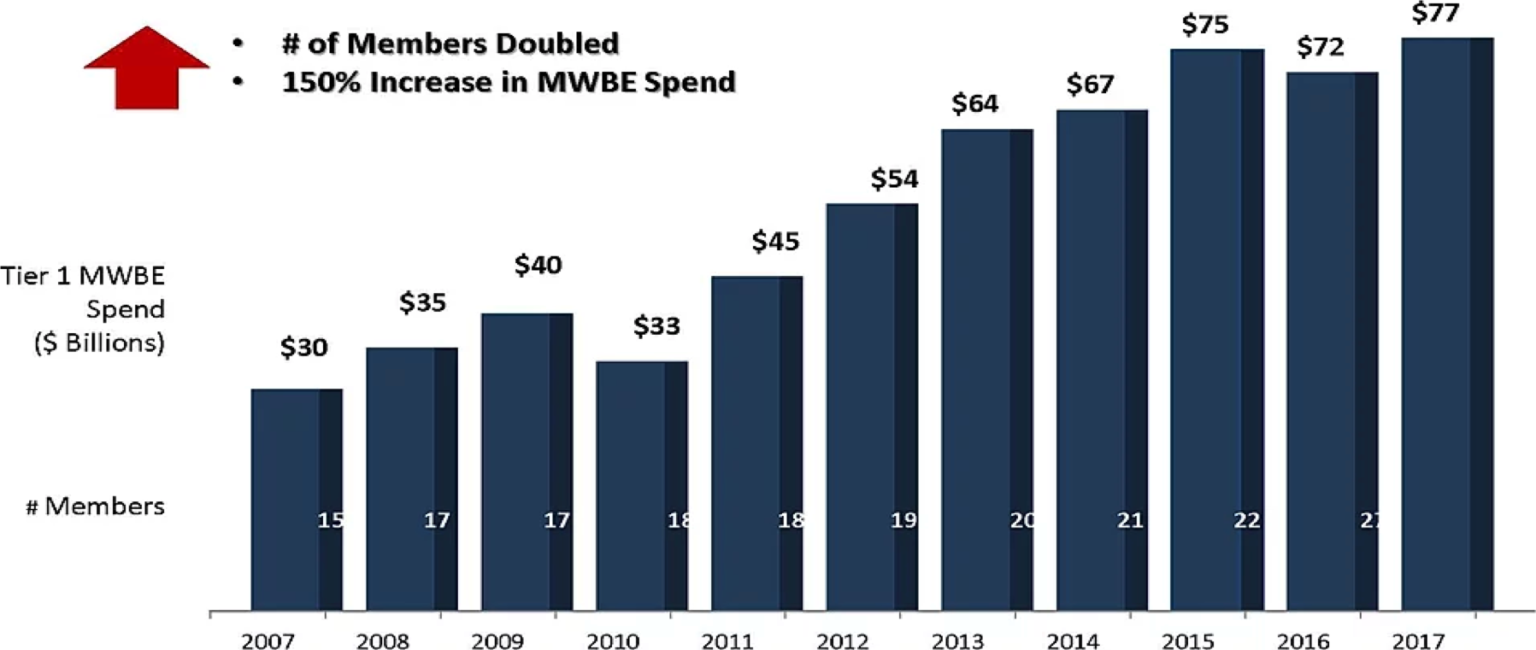

We will return to the potential of federal procurement efforts in subsequent newsletters. For now, we want to highlight how federal efforts, pursued over multiple decades, have stimulated commitments by large corporations. In 2001, for example, the Billion Dollar Roundtable (“BDR”) was created. Today, the BDR is an organization of 28 major companies “that achieved spending of at least $1 billion with minority and women-owned suppliers” in Tier-1 spending (i.e., companies that work directly with large OEM companies). The number of BDR organizations nearly doubled between 2007 and 2017 and spending has increased at a faster rate, growing from $30 billion in 2007 to $77 billion by 2017.[5]

Figure 1 https://www.billiondollarroundtable.org/statistics

Within the BDR, legacy automotive companies comprise 32% of Minority- and Women- Owned Business Enterprises (MWBE) spending by all BDR companies, followed by information technology and healthcare at a respective 14%. Since longevity in supplier diversity is often correlated with an organization’s capacity and efficiency to engage in such programming, the early entrance of Detroit auto makers into the field is likely a major determinant for how they still maintain such a large share of billion-dollar supplier diversity programs.[6]

Another shining example is AT&T, which has been engaged in supplier diversity for over 50 years and recently announced they are on target to achieve $3 billion in spend solely with Black-owned businesses and a total spend of more than $173 billion with minority, woman, service-disabled veteran, and LGBTQ+ businesses over the program’s lifespan. In 2018, they surpassed their previous diverse supplier spend by $700 million demonstrating how established firms have tremendous room to grow. According to AT&T, these gains were attributed to “a refreshed vision” based on the following pillars: diverse supplier spend and utilization; diverse job creation and force impact; diverse business fostering, advocacy and ‘tier 2’ supplier growth.[7]

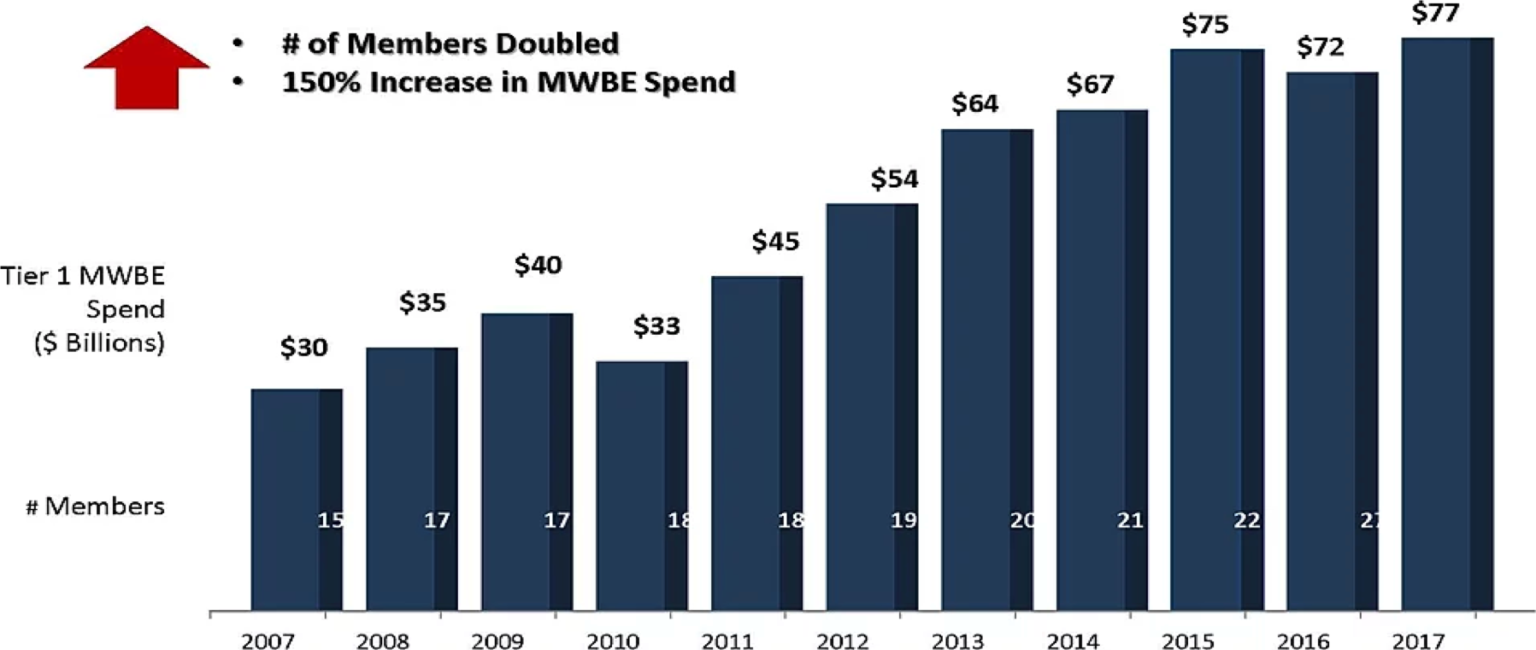

The average BDR firm spend with diverse suppliers in 2017 was $2.9 billion, declining from its peak of $3.6 billion in 2015. Despite the relative decline in Tier 1 spending for MWBE suppliers, the total spend by just the 28 companies in the BDR in 2017 surpassed the total federal 8(a) set-aside procurement by $50 billion dollars, demonstrating the enormous value of corporate procurement.[8]

Outside of the BDR, other helpful information on the state of supplier diversity comes from membership organizations like the National Minority Supplier Diversity Council and CVM Solutions, a firm that helps corporations design and deliver supplier diversity programs.

Our assessment of BDR and other supplier diversity efforts, yield the following initial observations:

First, we need a steep change in the quality and transparency of procurement data. We celebrate the scale of corporate spending, at the aggregate level, that supports MWBE firms. But this information is often revealed as a marketing tool, particularly during volatile periods like the one we are experiencing today. Granular and actionable information, uniformly collected and publicly available via a centralized source is needed to enhance accountability, evaluate corporate strategies and identify gaps in procurement efforts. The lack of such information presents a tremendous barrier to understanding the efficacy of these programs and the public and private strategies and intermediaries necessary to move the dial on the number, size and sector representation of such firms on a systemic basis. Similar to how supplier diversity is primarily advanced under the scope of corporate responsibility, increased transparency could be another value that corporations adopt if defined as a benefit to the public-good.[9] Frankly, we may need a federal Supplier Diversity Disclosure Act, covering corporations, universities, hospitals and financial institutions, to bring norms and routines to the entire system.

Second, corporations need to examine their Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) to ensure they are focused on maximum impact. A recent analysis by CVM showed that the KPIs used by companies included:

-

Diverse Spend: How much money a company is spending with diverse suppliers.

-

Diverse Count: The number of diverse suppliers that a company executes contracts with.

-

Economic Impact: How doing business impacts the economy, specifically the local economy where a company’s suppliers are located and do business.

-

Cost Savings: The ratio of organizational spending to revenue over time.

-

Revenue Impact: A program’s impact on revenue earned and projected.

-

Market Share: A company’s sales in relation to the overall revenue of their industry.

-

Deals Won: How many diverse suppliers were contracted within the stipulated time frame.

-

Deals Lost (Due to Disqualified Suppliers): deals lost because suppliers don’t meet a company’s qualification criteria

-

Tier 2 Diverse Suppliers: the diversity efforts of a company’s direct (Tier 1) diverse and non-diverse suppliers in terms of their diverse spend and diverse count.[10]

While these metrics have become more robust over time, they are mostly focused on the impact these efforts have on the company, and/or the company’s ability to measure itself against other companies’ efforts or their previous or future goals. But other metrics are necessary to understand the impact these programs have on the communities themselves. What’s most important from the community perspective is the financial impact these programs have on the longevity of the companies they spend on and particularly how these small businesses are able to grow due to the support of large corporate investment and inclusion.[11]

Third, corporations with longstanding supplier diversity programs have developed best practices that should be universally implemented. A key component of the growth of a supplier diversity program is the role of high-level leadership in pushing company culture to recognize supplier diversity as a key component of the company’s mission, budget, and internal programming. Establishing clear benchmarks to ensure organizational accountability is important to establishing a robust supplier diversity system, and in fact, “97% of the Fortune 500 companies set percentage dollar goals on supplier diversity.”[12]

Yet challenges on both the supply and demand side were revealed in a 2019 CVM report on the State of Supplier Diversity:

-

Supplier Challenges

-

Difficulty in being discovered by bigger companies

-

Purchasing, procurement, and other decision-makers not attuned to how their supplier diversity programs work

-

An underlying fixation on the bottom line rather than diversity[13]

-

Corporate Challenges

-

Struggle in communicating benefits of supplier diversity to C-Suite staff and individual departments

-

Adequate staff resources; building engagement and participation; ensuring the accuracy and integrity of supplier diversity data

-

Decentralized decision-making reduces time available to influence the state of suppliers considered[14]

Finally, there is a dearth of local intermediaries with the capacity, capital and community standing to match the procurement demand of large companies with the supply of MWBE companies that are either qualified to fulfill the demand or could be qualified with sufficient coaching and support. Cincinnati offers a model for other cities to consider. Building on Procter & Gamble’s (P&G) early commitment to supplier diversity in the 1970s, the metro has developed a sophisticated network of organizations to mentor companies and play helpful match-making roles. P&G’s leadership preceded the creation of the Ohio Minority Supplier Development Council and Cincinnati’s implementation of its own minority-owned business set aside ordinance in 1978.[15] These simultaneous developments helped create an ecosystem of private and public actors implementing similar tools to aid the formation, stabilization, and growth of minority businesses in the Cincinnati region and beyond.

A key engine within Cincinnati’s model is the Minority Business Accelerator, housed within the Cincinnati Regional Chamber of Commerce. The MBA advances development of sizable minority businesses as part of a regional effort around business and talent attraction. “People are drawn to where they perceive opportunity for everyone.”[16]

The Cincinnati Minority Business Accelerator maintains a list of Goal Setter Companies, including P&G, that collectively commit to a set of expectations to “diversify their supplier pipeline and fuel innovation while improving [Cincinnati’s] local community and economy.”[17] The list consists of 42 companies ranging from legacy firms like Kroger’s and P&G to newly created partnerships like the Uptown Consortium, a coalition of anchors supporting the growth of five Cincinnati neighborhoods (UC). The inclusion of UC demonstrates how an established supplier diversity ecosystem encourages new organizations to be a part of this network of institutions and design their own internal metrics to abide by similar standards. Key components of the Goal Setter expectations are that companies establish MBE set-asides for at least two years, share internal supplier diversity and MBE development methodologies, and collaborate to share success stories and best practices with other Goal Setter firms.

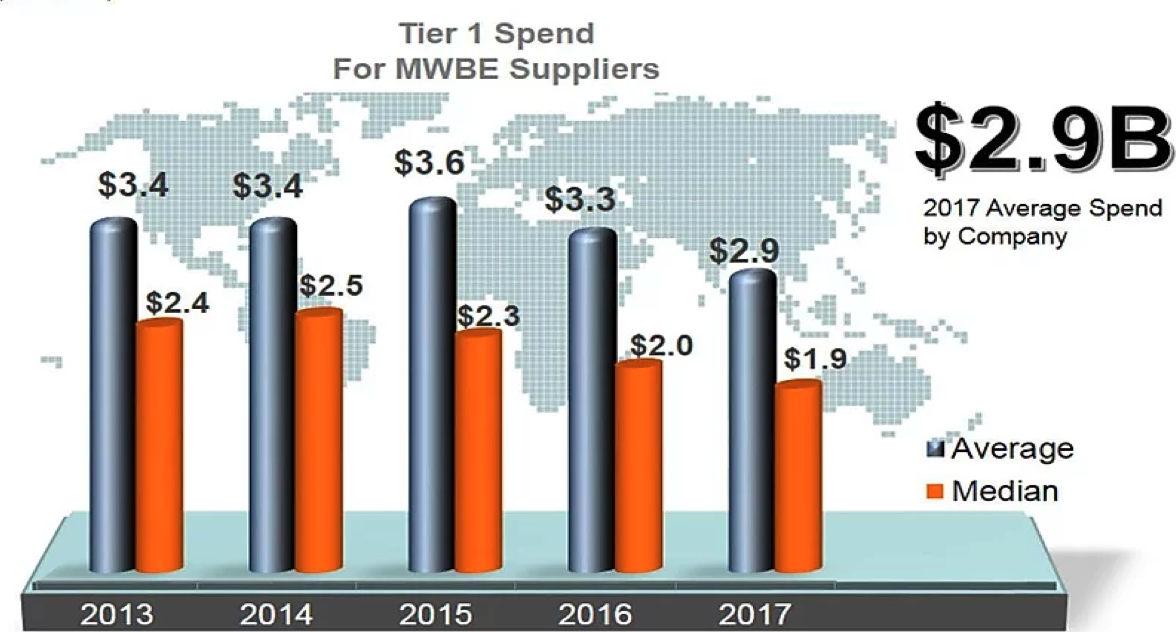

Cincinnati’s success has been nationally recognized. A 2019 study conducted by LendingTree[18] looked at the 50 largest U.S. metros and considered the following:

-

The percentage of self-employed minorities in each metro;

-

Minority businesses ownership parity index (a score based on the ratio of businesses owned by minorities compared to the population of minorities in the area);

-

The percentage of minority-owned businesses that took in at least $500,000 in revenue; and

-

The percentage of minority-owned businesses that have been in operation for at least six years.

As the below chart shows, Cincinnati performs markedly well on the last two metrics.

Figure 2 https://www.lendingtree.com/business/where-minority-entrepreneurs-succeeding/

Cincinnati’s model and approach are adaptable and implementable in any city and metropolis willing to dedicate the resources and cultivate a similar “purpose-driven” ecosystem that understands the economic potential of a local economy that values and supports its minority-owned entrepreneurial community.

Conclusion

As the United States begins to weigh different options for growing Black-owned businesses, we feel strongly that demand access needs to play a larger role than it has in the past. The data collected and research conducted in the supplier diversity field pales in comparison to what exists on the capital side. Well capitalized intermediaries at the local level either do not exist or are seriously under-resourced. Over the past several months, we have received a national wake up call. Will we respond at scale?

Aiyah Josiah-Faeduwor is a current dual MBA and Master in City Planning candidate at MIT’s Sloan School of Management and Department of Urban Studies and Planning respectively and is currently a Graduate Research Analyst at the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University.

Avery Harmon is a Master in City Planning candidate at the University of Pennsylvania’s Weitzman School of Design and is currently a Graduate Research Analyst at the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University.